The Project

A pilón, traditional women’s tool for the preparation of coffee, grains and medicinal remedies.

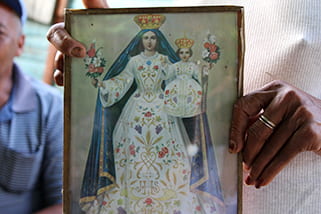

La Virgen de los Remedios

An encounter between pueblos in la cañada.

The Healers Project: Decolonizing Knowledge Within Afro-Indigenous Traditions is a collaborative research project built as a result of our journeys within Caribbean communities throughout the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Pacific Northwest region. In 2016, after four years of meeting and spending time with Caribbean women that keep their Afro-Indigenous, Indigenous and Afro-descendant healing traditions alive, we were inspired to conceptualize a project that validates their knowledge in a world where Eurocentric notions of health and medicine vilify and dismiss them. As we pursued the project, the women we interviewed and document here have shared a collective investment in sharing their knowledge across generations at a time when migration disrupts the ways in which their communities have passed down knowledge.

In our conversations with these women elders, we realized that a powerful avenue for the dissemination of knowledge exists within the digital humanities. Along with the UO Digital Scholarship Team, and UO Ethnic Studies and Journalism student Miguel Pérez, this website came together to provide open access to our interviews. In addition, we realized we could also develop an ethnobotanical guide of their gardens – information that their communities, both at home and in Diaspora could access over time. Secondly, we realized that students, the general public, and researchers could also benefit from learning and participating in the intergenerational transmission of traditional healing methods and knowledge production.

Here we engage our shared commitment to decolonize how we conceptualize and validate knowledge in the Americas. Our methodology disrupts Eurocentric and elitist documentation practices that privilege the ethnographer’s authority while relegating our communities to a secondary status. All of the work produced from our time with these amazing women, elders, healers required us to push against the boundaries of what is deemed rational or reasonable by Occidental frameworks. In order to engage healing and social change from the perspective of Afro-Indigenous healers, we had to not just observe what we were experiencing and being told, we had to also examine our own beliefs, values, and experiences of what the world is. We had to put aside our training as “experts,” in order to understand that we were being witness to and being welcomed into whole worlds that we knew nothing about. This work asks us to engage in the decolonial act of theorizing in conversation with those sites of knowledge production rendered illegible by both colonizers and secular anti-colonial thinkers.

This work both seeks to interrogate and to interrupt the colonial gaze that historically vilifies and demeans our elders as “uneducated,” or “simple,” or “primitive,” and that deems their knowledge simply “folklore,” “popular religion,” or “superstition.” What these words and this gaze fail to account for are the many ways in which our elders create meaning in their lives, and the lives of their families and communities – through knowledge of home, of land, and of medicine. What these words and this gaze fail to account for are the ways in which Western epistemologies privilege masculine authority, written language, school-based learning, and wealth produced through extractive capitalism. As the African-American saying goes, “These elders know what time it is.” In order to interrupt the colonial gaze that has historically vilified Afro-Indigenous women healers, we conversed with them directly and actively recognized their societal role as knowledge producers. We – two women with PhDs – understood that our degrees were “wet paper” (papel mojado) if we walked in with the attitude that we already knew more than the elders who were taking time to speak with us. So, we walked humbly so that we could learn, and be schooled, about knowledge that has been preserved over generations, in relationship to place and land and family.

Their knowledge and perspectives offer us tools — through storytelling, healing modalities, crafts, dance, ritual, and music — to confront racism, gender inequities, xenophobia and the very real threats produced by limited access to healthcare. By documenting the ways in which women healers conceptualize and produce knowledge, we provide access to and validate epistemic systems that have been historically silenced or devalued; recognize how those epistemic systems have enabled the empowerment of indigenous, Afro-indigenous, and Indigenous women in different contexts; and, open spaces to reflect on how healing methods derived from indigenous, Afro-indigenous and Indigenous traditions speak to contemporary social concerns.

Dr. Ana-Maurine Lara and Dr. Alaí Reyes-Santos

Caribbean Women Healers

UO Libraries| Digital Scholarship Center

This work is In Copyright-Educational Use Permitted.

Contact the Caribbean Healers Project for additional use.