About

A pilón, traditional women’s tool for the preparation of coffee, grains and medicinal remedies.

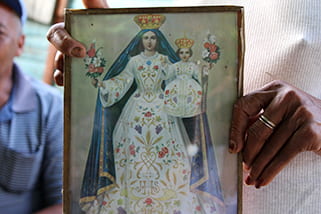

La Virgen de los Remedios

An encounter between pueblos in la cañada.

The Healers Project

The Healers Project: Decolonizing Knowledge Within Afro-Indigenous Traditions is a collaborative research project emerging from our experiences of building community alongside Indigenous, Afro-descendant, and Afro-Indigenous peoples throughout Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Pacific Northwest region (PNW).

The project has been completed in two phases. In the first one we focused on Caribbean women healers in the Caribbean and the U.S. Pacific Northwest. We published the original Caribbean Women Healers digital humanities site in Spring 2020. In the second phase we placed the interviews with Caribbean women healers in conversation with other Indigenous and Black communities in the U.S. Pacific Northwest and published a Spanish-language version of the website. This second phase is now known as The Healers Project and was launched in Spring 2024.

In the last three years, we also increased our Caribbean interview collection in Puerto Rico and the PNW; added more gathering grounds to our visual ethnobotanical survey; included a collection of interviews with Dominican ceremonialists stewarding healing practices around the figure of Ogún-an Afro-descendant misterio or orisha-; expanded the scope of the site to more intentionally include two-spirit peoples and cis-gender men; incorporated more multimedia educational tools under the Resources tab; updated the bibliography, including a guide with readings for primary school children; published an e-book in Spanish; and the new tab on the top menu takes you to Conversa’o which features essays and multimedia digital pieces in English and Spanish originally authored by our research and digital humanities team and interlocutors in the Caribbean and the PNW.

In our conversations with healers year after year we came to understand that Caribbean healers are embedded in the everyday practice of keeping alive traditional ecological knowledge; and that traditional knowledge keepers are healers themselves restoring landscapes and communities facing the onslaught of colonization. All interviewees-no matter where they are or how they identify themselves-are invested in healing peoples, lands, and waters through the revitalization of communities’ medicinal knowledge, histories, ceremonies, and environmental practices vilified, dismissed, and policed by colonial institutions.

A little bit about our history . . .

In 2016, after four years of meeting and spending time with Caribbean women that keep their Indigenous, Afro-descendant, and Afro-Indigenous healing traditions alive in the islands and the U.S. Pacific Northwest, we were inspired to conceptualize a project that validates their knowledge in a world where Eurocentric notions of health and medicine vilify and dismiss them. As we pursued the project, the women we interviewed, and document here have shared a collective investment in sharing their knowledge across generations at a time when migration disrupts the ways in which their communities have passed down knowledge.

In our conversations with these women elders, we realized that a powerful avenue for the dissemination of knowledge exists within the digital humanities. Along with the UO Digital Scholarship Team, this website came together to provide open access to our interviews. In addition, we realized we could also develop an ethnobotanical guide of their gardens. This is information that their communities, both at home and in diaspora, could access over time. Secondly, we realized that students, the general public, and researchers could also benefit from learning about and participating in the intergenerational transmission of traditional healing methods and ecological knowledge that constitutes the website.

Scholarship regarding Caribbean diasporas continues to privilege the East Coast, Chicago, and Florida; scholarship discussing Afro-descendant, Indigenous and Afro-Indigenous stories in the PNW often doesn’t account for Caribbean diasporas. As Caribbean women living in the PNW, we realized that our Caribbean diasporic communities are invisible. The Healers Project recognizes how we sustain traditional healing practices through constant travel between the islands and the PNW. Our hope is that The Healers Project creates new opportunities for research in the region; that we may better serve and support communities oftentimes feeling a deep sense of cultural loss, isolation, and displacement so far away from home and fellow caribeñes. It is also essential to name Caribbean Indigenous, Afro-descendant, and Afro-Indigenous traditional knowledges to counter how our ways of being and knowing can be easily dismissed by U.S. dominant ideas of Indigeneity and Blackness; such dismissals worsen Caribbean communities’ experiences of cultural isolation and exclusion in the PNW.

By putting Caribbean and non-Caribbean Indigenous and Afro-descendant healers in conversation with one another, the second phase of the site places Caribbean peoples in a set of unexpected and yet real, existing, networks of solidarity and kinship with other communities in the region. It also hints at existing efforts to strengthen relationships between PNW Indigenous, Afro-descendant, and Afro-Indigenous communities, the Caribbean and Latin America, such as a trip to the Dominican Republic in 2022 by PNW-based tribal, Caribbean, African American, and Mexican environmental leaders, and a recent delegation of Indigenous and Afro-Indigenous women from the PNW to Brazil in 2024.

Engaging Caribbean presence in the PNW has become even more significant as Puerto Ricans’ presence in the PNW drastically increased after Hurricane Maria devastated the island in 2017; as we find Dominican businesses that allow Dominican immigrants to send remittances home from Oregon and Alaska; as Cubans relocate here in more recent waves of immigration in the past twenty years; as Cuban, Dominican, and Puerto Rican restaurants, kiosks, and other food businesses begin to enchant the region with their unique cuisines, alongside Haitians, Jamaicans, Guyanese, and Trinidadians.

About our approach . . .

The Healers Project engages our shared commitment to decolonize how we conceptualize and validate knowledge in the Americas. Our methodology disrupts Eurocentric and elitist documentation practices that privilege the ethnographer’s authority while relegating our communities to a secondary status. All the work produced from our time with these amazing healers required us to push against the boundaries of what is deemed rational or reasonable by Occidental frameworks. To engage healing and social change from the perspective of Afro-Indigenous healers, we had to not just observe what we were experiencing and being told, we had to also examine our own beliefs, values, and experiences of what the world is. We had to put aside our training as “experts” in order to understand that we were being witness to and being welcomed into whole worlds that we knew nothing about. This work asks us to engage in the decolonial act of theorizing in conversation with those sites of knowledge production rendered illegible by both colonizers and secular anti-colonial thinkers.

This work both seeks to interrogate and to interrupt the colonial gaze that historically vilifies and demeans our elders as “uneducated,” or “simple,” or “primitive,” and that deems their knowledge simply “folklore,” “popular religion,” or “superstition.” What these words and this gaze fail to account for are the many ways in which our elders create meaning in their lives, and the lives of their families and communities – through knowledge of home, of land, and of medicine. What these words and this gaze fail to account for are the ways in which Western epistemologies privilege masculine authority, written language, school-based learning, and wealth produced through extractive capitalism.

As the African American saying goes, “These elders know what time it is.” To interrupt the colonial gaze that has historically vilified Afro-Indigenous healers, we conversed with them directly and actively recognized their societal role as knowledge producers. We – two women with PhDs – understood that our degrees were “wet paper” (papel mojado) if we walked in with the attitude that we already knew more than the elders who were taking time to speak with us. So, we walked humbly so that we could learn, and be schooled, about knowledge that has been preserved over generations, in relationship to place and land and family.

Their knowledge and perspectives offer us tools — through storytelling, healing modalities, crafts, dance, ritual, and music — to confront racism, gender inequities, xenophobia and the very real threats produced by limited access to healthcare and healthy foods. By documenting the ways in which healers conceptualize and produce knowledge, we provide access to and validate epistemic systems that have been historically silenced or devalued; recognize how those epistemic systems have enabled the empowerment of Indigenous, Afro-descendant, and Afro-Indigenous peoples in different contexts; and, open spaces to reflect on how healing methods derived from Indigenous, Afro-descendant, and Afro-Indigenous traditions speak to contemporary social concerns.

Dr. Ana-Maurine Lara and Dr. Alaí Reyes-Santos, and the UO Libraries